Impact of Strong Law in Achieving Effective Port Economic Regulation in Nigeria

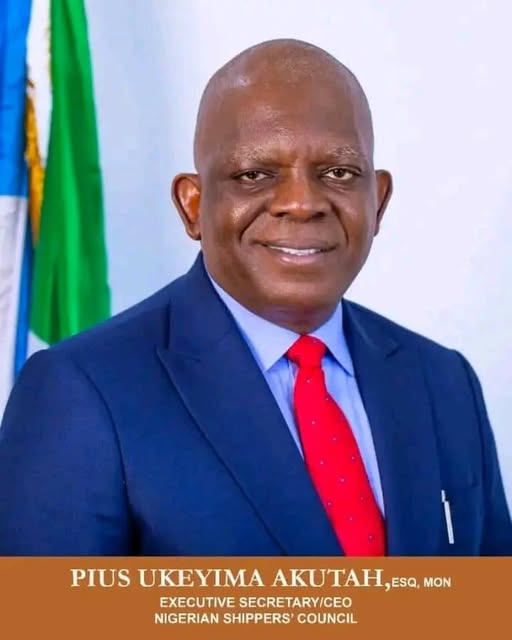

Dr. Akutah

By Pius Akutah Ukeyima, PhD

It is indeed a privilege to be called upon to address this gathering to discuss a topic that is critical to our nation’s economic growth. The emergence of one of our own, the Comptroller General of the Nigerian Customs Service, as Chairperson of the World Customs Organization (WCO) Council, shows the level of confidence that the trade/ shipping world has in Nigeria. This is due largely to some of the reforms embarked upon by the current administration of President Bola Ahmed Tinubu GCFR since assuming office over two years ago.

It is instructive to state at this point that my dear friend, the Comptroller General of the Nigerian Customs Service, is the first Nigerian and one of the few Africans to head the WCO Council in its 73-year history. This is a landmark achievement for the Country and the Continent at large. Please permit me to once again congratulate the CG on this rare achievement, which was attained out of his shared determination to reposition the Nigeria Customs Service by introducing reforms which have positively impacted on the nation’s economy. The WCO Council Chairmanship is an opportunity not only to elevate Nigeria’s voice at the table but to reinforce the domestic reforms that would enable our ports and our trade corridors to serve the Nation’s economy more efficiently and fairly.

I have been asked to speak on the topic- ‘The Impact of Strong Law in Achieving Effective Port Economic Regulation in Nigeria’. There cannot be a better time to speak on this topic than now, when the Nigerian Shippers’ Council, which in the past was saddled with the major responsibility of protecting the interests of Shippers and others, is in the process of transitioning from its traditional role to an effective role as the economic regulator in the Nigerian Port, a function we have been carrying out since 2015 when the Council was appointed the Regulator of the Port by the then President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria.

Regulation goes to the root of every sector. For there to be efficient and effective service delivery, a regulator is needed who serves as an impartial arbiter to protect the interests of all industry players/ providers and users of shipping and port services. The transformation being witnessed in the telecommunications and aviation sector, for instance, could be attributed to the establishment of the Nigerian Communications Commission (NCC) and the Nigerian Civil Aviation Authority (NCAA). These two agencies were created through their various enabling Acts, to wit, the Nigerian Communications Act, 2003 and the Civil Aviation Act, 2022 respectively. These agencies serve as regulators and moderators for the telecom and aviation sector and set rules and regulations in accordance with their enabling laws.

Legal regimes on Port Economic Regulations in Nigeria.

The Nigerian Shippers’ Council, which is the nation’s Port Economic Regulator, currently operates on some legal instruments. Firstly, the Nigerian Shippers’ Council Act, Cap133 LFN; Nigerian Shippers’ Council (Port Economic Regulator) Order, 2015; the Nigerian Shippers’ Council (Port Economic) Regulation, 2015, and other subsidiary legislations.

The aforesaid Act and subsidiary Regulations set up the Council to protect shippers against unfair trade practices and to serve as an advisory arm to the Federal Government on matters relating to the transportation of goods to and from Nigeria, among other functions. In addition, the Presidential Order, on the other hand, empowers the Council to serve as the Port Economic Regulator for the Nigerian ports. The Order was made by the President pursuant to the powers conferred on him under Sections 5 and 148 of the 1999 Constitution of the FRN. The 2015 Regulation, on the other hand, was made by the Honourable Minister of Transportation to set out the guidelines under which the Port Economic Operator is to operate and was made pursuant to Section 9 of the NSC Act which empowers the Honourable Minister to so act. The regulation, among others, highlights the regulated service providers within which the economic regulator is to regulate. It sets conditions within which providers and users of shipping and port services should operate in the ports industry and, of course, provides penalties to ensure compliance.

The above instruments have been what the Council has been using in carrying out its regulatory functions at the Nigerian Ports. These legal frameworks, as they exist today, are bereft of some necessary ingredients of economic regulation as obtained in other jurisdictions.

Today, speaking on the topic I have been mandated to discuss, I wish to focus on three connecting propositions to help us do justice to the topic:

A. Strong, clear, and enforceable laws are a prerequisite for credible port economic regulation.

B. Competent laws — aligned with institutional capacity and enforcement — deliver measurable benefits: competition, investment, lower trade costs and predictability.

C. Nigeria’s new standing at the WCO should be matched by domestic legal reform and rigorous application to secure the full economic benefits of our ports.

1. Why law matters: foundations of predictability and fairness

Ports are both marketplaces and bottlenecks. They are the focal point where public and private interests collide. Without clear rules, monopolies flourish, fees become opaque, concessions are abused and costs rise for importers and exporters. For example, cargo dwell time in Nigerian ports is among the lengthiest in West Africa, averaging 20-25 days, compared to 3-7 days on average in places like Cotonou, Tema, or Durban. This delay is largely due to bureaucratic bottlenecks, overlapping agencies, and lack of automation. The long dwell time increases demurrage and storage costs for importers/exporters.

But a strong law within the maritime industry anchors:

• Institutional independence: Regulators insulated from political pressure, like the UK’s Office of Rail and Road, which supervises port competition rules independently .

• Customs reform and trade facilitation: The WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement, which Nigeria has ratified, shows how binding commitments to transparency and simplified border procedures can reduce delays and costs .

• Labour stability: The International Labour Organization’s Maritime Labour Convention (MLC 2006) ensures fair working conditions in ports, reducing strikes and disruptions .

• Safety and environment: The MARPOL Convention and EU directives on port reception facilities show how environmental compliance laws prevent pollution while keeping ports attractive to global carriers

A modern port economic regulator requires a legal mandate that sets out:

(a) the regulator’s objectives (efficiency, fair access, price oversight where appropriate), (b) its powers (licensing, price review, market investigations, dispute resolution), and

(c) safeguards (transparency, appeal procedures, and clear standards for state support).

The Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore Act provides a useful model: by statute it gives the regulator powers to create an economic regulatory framework that promotes and safeguards competition in port services and facilities. That legal clarity has been central to Singapore’s ability to run world-class, commercially vibrant, and sustainable ports .

2. Legal design plus enforcement equals results — international lessons

Let me give three short examples where legal frameworks and active enforcement helped deliver balanced markets and better outcomes:

• Singapore — statutory regulator + commercial governance: Singapore’s legal framework (the MPA Act and supporting instruments) explicitly empowers the regulator to oversee port services, set licensing rules and coordinate land/sea logistics planning. The effect has been a predictable regulatory environment that attracts capital and supports efficient operations across terminals, pilotage and towage. The statutory approach links economic regulation to national maritime strategy . Pull out quote: “A statutory regulator with clear legal powers creates predictability and investor confidence, aligning port operations with national maritime strategy”.

• European Union — state aid discipline and port investments: The EU has applied rigorous state-aid rules to port infrastructure spending, requiring transparency and compatibility with competition objectives before public support is given. The European Commission’s decisions and state-aid framework have constrained arbitrary subsidies that distort competition between ports and ensured that public funds are used consistently with the single market. For example, the European Commission’s state-aid decisions on port investments fix standards for notification, transparency and proportionality. This legal architecture reduces the risk of inefficient duplication and unfair competitive advantages .

“Strict state-aid rules prevent distortion and ensure that public funds are used transparently and in line with competition objectives”

• United States – Labour and Safety Frameworks: U.S. port regulation combines economic oversight with labour stability under laws like the Taft-Hartley Act, ensuring industrial peace in critical infrastructure. This shows how embedding labour law within port regulation sustains continuity in trade flows .

“Embedding labour and safety law within port regulation maintains industrial peace and secures continuity of trade flows”.

These cases teach a simple lesson: statute + institutional independence + enforcement = credible market rules. Where one of these elements is missing — for example, laws without enforcement resources, or enforcement vested in politically dependent bodies — outcomes suffer.

3. Nigeria’s situation: the opportunity and the gaps

Nigeria’s ports are central to our national economy. They are also areas of recurring friction: congestion, disputes over terminal access and charges, and opaque concessioning and state support arrangements. If we imagine the WCO Chairmanship as an instrument of global influence, it must be paired with visible domestic reforms that demonstrate that we practice what we preach on customs governance, transparency and commercial regulation.

Specific legal weaknesses that require attention include:

• Unclear economic regulatory mandate — a statutory framework that clearly defines economic regulation for shipping and port services, across terminals, pilotage, towage and stevedoring. Example: In Nigeria, multiple agencies overlap in regulating port tariffs and services. This often leads to conflicting directives. For instance, in 2019, freight forwarders protested contradictory tariff notices issued by NPA and terminal operators, causing confusion and delays in cargo clearance.

• Inadequate competition safeguards — rules to prevent anti-competitive coordination among dominant port service providers and to control discriminatory pricing or rebates. Example: Nigeria’s port system is dominated by a few terminal operators, and complaints of price-fixing and discriminatory rebates are frequent. In 2021, clearing agents accused some terminal operators of colluding to increase handling charges at Tin Can and Apapa ports, leaving shippers with little choice due to lack of competition.

• Opaque state support and concessions — legal rules for notification, transparency and competitive tendering for port infrastructure and concession contracts. Example: Since port concessioning in 2006, stakeholders have repeatedly raised concerns about the lack of transparency in concession renewals and state support. For example, concession agreements worth billions were renewed in 2021 without competitive bidding, prompting industry groups to call for more open tender processes.

• Weak dispute resolution mechanisms — specialised, speedy forums to resolve port commercial disputes and tariff complaints. Example: Disputes over port charges often clog Nigeria’s courts for years. In 2020, freight forwarders complained that unresolved tariff disputes were costing shippers millions in demurrage and storage fees as cases dragged on without timely resolution. This discourages smaller players who cannot afford prolonged litigation

Addressing these gaps will foster private investment, reduce trade costs, and increase government revenue through more transparent concessioning and predictable tariffs.

4. What strong laws should look like in practice

I propose a number of legal instruments and principles that should be considered:

• A Port Economic Regulation Act — a single statute that (a) defines the regulator’s objectives (promote efficiency, fair access and competition), (b) grants licensing and investigative powers, (c) empowers price monitoring and interim remedies where operators hold market power, and (d) provides for transparent rule-making and appeal.

The drive for this is already under way with the proposed Nigerian Port Economic Regulator Bill (NPERA Bill [currently awaiting Presidential assent]) where the Federal government seeks to properly equip the Nigerian Shippers Council, being the parastatal that is saddled with the responsibility of Port Economic Regulatory functions through A Presidential Order granted in 2015; to monitor pricing and provide for transparent rulemaking in the maritime industry. Singapore’s statutory model offers a helpful precedent .

• Competition law integration and sector guidelines — the existing competition law, namely the Federal Competition and Consumer Protection Act (FCCPA) 2018, must be applied to port markets. Where necessary, sector-specific guidelines (e.g., on rebates, bundling, exclusive deals) are produced jointly by the regulator (Nigeria Shippers Council) and the competition authority (FCCPC). The EU and UK frameworks show the importance of competition scrutiny in public support and port operations .

• State support transparency rules — We must require public notification of investment or support for port infrastructure, with objective criteria to assess compatibility with national economic goals and competition. The EU’s state-aid practice shows how transparency disciplines market distortions .

• Data, benchmarking and independent monitoring — The law must also require publication of performance metrics (dwell time, crane rates, berth productivity). Regular public benchmarking creates political incentives for reform and arms shippers with information. Australia’s port monitoring reports are a good example of how data drives policy .

• Specialised dispute resolution — We must also provide for expedited arbitration centre for port disputes, reducing transaction costs and providing predictable outcomes, encourages investment.

• Institutional Independence – Regulators must be financially autonomous, with leadership shielded from political pressure.

• Customs Facilitation Alignment – Implement the World Trade Organizations (WTO’s) Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) fully, leveraging digital clearance to reduce bottlenecks.

5. Linking domestic reform to our WCO Chairmanship

Nigeria’s chairing of the WCO Council places our customs leadership at the centre of global best practice on trade facilitation and customs governance. This international leadership must be mirrored at home: robust customs operations deliver little if the port economic framework remains permissive of rent-seeking and monopoly pricing.

By pairing WCO leadership with domestic legal reform we will:

• Demonstrate to multilateral partners and investors that Nigeria is committed to transparent, rule-based port governance;

• Improve trade facilitation outcomes — fewer delays, lower costs, better compliance — which benefits customs revenue collection and national competitiveness; and

• Leverage international best practice, technical assistance and harmonised standards through the WCO platform for domestic reform.

The world is watching Nigeria, and credibility abroad will only be matched by credibility at home.

6. Immediate recommendations

To convert law into outcomes I recommend these immediate steps:

1. Passing into law of the Nigerian Port Economic Regulatory Agency Bill — full stakeholder support.

2. Establish a data-driven monitoring programme — with quarterly KPI’s.

3. Adopt state-support notification rules — for infrastructure projects.

4. Strengthen enforcement capacity — through investigators and a specialist dispute resolution stream.

5. Enhance labour stability by fully implementing the MLC.

Conclusion

Strong law is not an end in itself. It is an instrument for creating predictable markets, for not only protecting shippers and consumers but also regulating providers and users of shipping and port services, for attracting productive investment, and for ensuring that public resources allocated to ports are used in ways that generate national income.

Nigeria’s elevation to the WCO Council Chairmanship is a moment of moral and political authority. Let us use that authority to cement our domestic institutions with laws that are clear, enforceable, and oriented towards competition, transparency, customs trade facilitation, safety, labour stability, and long-term national prosperity. Yet, it is pertinent to state that no matter how strong and beautiful our laws are, they cannot serve the purpose for which they were created without effective implementation measures. And implementation does not take place in a vacuum. The critical stakeholders in the industry must first acknowledge the binding force of these laws and accept that effective port economic regulation requires their full buy-in. Only when stakeholders own the process and elevate economic regulation as a collective priority can we truly facilitate trade and drive economic growth.

The regulator must also be perceived and respected as an impartial arbiter—ensuring equity and fair play among all industry players. With collective commitment and trust, we can restore confidence in Nigeria’s shipping and ports sector, unlocking the vast potential of our marine and blue economy for national prosperity.

If we do so, our ports will not only move more cargo; they will move our economy forward—our marine and blue economy sector will flourish and impact positively on the nation’s economy.

*Being a paper delivered by the Executive Secretary/CEO, Nigerian Shippers’ Council, Dr. Akutah Pius Ukeyima Esq. (MON, FCILT, FlnsTA, Ph. D) on the occasion of the 2025 one day seminar organised by the League of Maritime Editors on the 30th of September, 2025, at Rockview Hotel, Apapa, Lagos.

It is indeed a privilege to be called upon to address this gathering to discuss a topic that is critical to our nation’s economic growth. The emergence of one of our own, the Comptroller General of the Nigerian Customs Service, as Chairperson of the World Customs Organization (WCO) Council, shows the level of confidence that the trade/ shipping world has in Nigeria. This is due largely to some of the reforms embarked upon by the current administration of President Bola Ahmed Tinubu GCFR since assuming office over two years ago.

It is instructive to state at this point that my dear friend, the Comptroller General of the Nigerian Customs Service, is the first Nigerian and one of the few Africans to head the WCO Council in its 73-year history. This is a landmark achievement for the Country and the Continent at large. Please permit me to once again congratulate the CG on this rare achievement, which was attained out of his shared determination to reposition the Nigeria Customs Service by introducing reforms which have positively impacted on the nation’s economy. The WCO Council Chairmanship is an opportunity not only to elevate Nigeria’s voice at the table but to reinforce the domestic reforms that would enable our ports and our trade corridors to serve the Nation’s economy more efficiently and fairly.

I have been asked to speak on the topic- ‘The Impact of Strong Law in Achieving Effective Port Economic Regulation in Nigeria’. There cannot be a better time to speak on this topic than now, when the Nigerian Shippers’ Council, which in the past was saddled with the major responsibility of protecting the interests of Shippers and others, is in the process of transitioning from its traditional role to an effective role as the economic regulator in the Nigerian Port, a function we have been carrying out since 2015 when the Council was appointed the Regulator of the Port by the then President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria.

Regulation goes to the root of every sector. For there to be efficient and effective service delivery, a regulator is needed who serves as an impartial arbiter to protect the interests of all industry players/ providers and users of shipping and port services. The transformation being witnessed in the telecommunications and aviation sector, for instance, could be attributed to the establishment of the Nigerian Communications Commission (NCC) and the Nigerian Civil Aviation Authority (NCAA). These two agencies were created through their various enabling Acts, to wit, the Nigerian Communications Act, 2003 and the Civil Aviation Act, 2022 respectively. These agencies serve as regulators and moderators for the telecom and aviation sector and set rules and regulations in accordance with their enabling laws.

Legal regimes on Port Economic Regulations in Nigeria.

The Nigerian Shippers’ Council, which is the nation’s Port Economic Regulator, currently operates on some legal instruments. Firstly, the Nigerian Shippers’ Council Act, Cap133 LFN; Nigerian Shippers’ Council (Port Economic Regulator) Order, 2015; the Nigerian Shippers’ Council (Port Economic) Regulation, 2015, and other subsidiary legislations.

The aforesaid Act and subsidiary Regulations set up the Council to protect shippers against unfair trade practices and to serve as an advisory arm to the Federal Government on matters relating to the transportation of goods to and from Nigeria, among other functions. In addition, the Presidential Order, on the other hand, empowers the Council to serve as the Port Economic Regulator for the Nigerian ports. The Order was made by the President pursuant to the powers conferred on him under Sections 5 and 148 of the 1999 Constitution of the FRN. The 2015 Regulation, on the other hand, was made by the Honourable Minister of Transportation to set out the guidelines under which the Port Economic Operator is to operate and was made pursuant to Section 9 of the NSC Act which empowers the Honourable Minister to so act. The regulation, among others, highlights the regulated service providers within which the economic regulator is to regulate. It sets conditions within which providers and users of shipping and port services should operate in the ports industry and, of course, provides penalties to ensure compliance.

The above instruments have been what the Council has been using in carrying out its regulatory functions at the Nigerian Ports. These legal frameworks, as they exist today, are bereft of some necessary ingredients of economic regulation as obtained in other jurisdictions.

Today, speaking on the topic I have been mandated to discuss, I wish to focus on three connecting propositions to help us do justice to the topic:

A. Strong, clear, and enforceable laws are a prerequisite for credible port economic regulation.

B. Competent laws — aligned with institutional capacity and enforcement — deliver measurable benefits: competition, investment, lower trade costs and predictability.

C. Nigeria’s new standing at the WCO should be matched by domestic legal reform and rigorous application to secure the full economic benefits of our ports.

1. Why law matters: foundations of predictability and fairness

Ports are both marketplaces and bottlenecks. They are the focal point where public and private interests collide. Without clear rules, monopolies flourish, fees become opaque, concessions are abused and costs rise for importers and exporters. For example, cargo dwell time in Nigerian ports is among the lengthiest in West Africa, averaging 20-25 days, compared to 3-7 days on average in places like Cotonou, Tema, or Durban. This delay is largely due to bureaucratic bottlenecks, overlapping agencies, and lack of automation. The long dwell time increases demurrage and storage costs for importers/exporters.

But a strong law within the maritime industry anchors:

• Institutional independence: Regulators insulated from political pressure, like the UK’s Office of Rail and Road, which supervises port competition rules independently .

• Customs reform and trade facilitation: The WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement, which Nigeria has ratified, shows how binding commitments to transparency and simplified border procedures can reduce delays and costs .

• Labour stability: The International Labour Organization’s Maritime Labour Convention (MLC 2006) ensures fair working conditions in ports, reducing strikes and disruptions .

• Safety and environment: The MARPOL Convention and EU directives on port reception facilities show how environmental compliance laws prevent pollution while keeping ports attractive to global carriers

A modern port economic regulator requires a legal mandate that sets out:

(a) the regulator’s objectives (efficiency, fair access, price oversight where appropriate), (b) its powers (licensing, price review, market investigations, dispute resolution), and

(c) safeguards (transparency, appeal procedures, and clear standards for state support).

The Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore Act provides a useful model: by statute it gives the regulator powers to create an economic regulatory framework that promotes and safeguards competition in port services and facilities. That legal clarity has been central to Singapore’s ability to run world-class, commercially vibrant, and sustainable ports .

2. Legal design plus enforcement equals results — international lessons

Let me give three short examples where legal frameworks and active enforcement helped deliver balanced markets and better outcomes:

• Singapore — statutory regulator + commercial governance: Singapore’s legal framework (the MPA Act and supporting instruments) explicitly empowers the regulator to oversee port services, set licensing rules and coordinate land/sea logistics planning. The effect has been a predictable regulatory environment that attracts capital and supports efficient operations across terminals, pilotage and towage. The statutory approach links economic regulation to national maritime strategy . Pull out quote: “A statutory regulator with clear legal powers creates predictability and investor confidence, aligning port operations with national maritime strategy”.

• European Union — state aid discipline and port investments: The EU has applied rigorous state-aid rules to port infrastructure spending, requiring transparency and compatibility with competition objectives before public support is given. The European Commission’s decisions and state-aid framework have constrained arbitrary subsidies that distort competition between ports and ensured that public funds are used consistently with the single market. For example, the European Commission’s state-aid decisions on port investments fix standards for notification, transparency and proportionality. This legal architecture reduces the risk of inefficient duplication and unfair competitive advantages .

“Strict state-aid rules prevent distortion and ensure that public funds are used transparently and in line with competition objectives”

• United States – Labour and Safety Frameworks: U.S. port regulation combines economic oversight with labour stability under laws like the Taft-Hartley Act, ensuring industrial peace in critical infrastructure. This shows how embedding labour law within port regulation sustains continuity in trade flows .

“Embedding labour and safety law within port regulation maintains industrial peace and secures continuity of trade flows”.

These cases teach a simple lesson: statute + institutional independence + enforcement = credible market rules. Where one of these elements is missing — for example, laws without enforcement resources, or enforcement vested in politically dependent bodies — outcomes suffer.

3. Nigeria’s situation: the opportunity and the gaps

Nigeria’s ports are central to our national economy. They are also areas of recurring friction: congestion, disputes over terminal access and charges, and opaque concessioning and state support arrangements. If we imagine the WCO Chairmanship as an instrument of global influence, it must be paired with visible domestic reforms that demonstrate that we practice what we preach on customs governance, transparency and commercial regulation.

Specific legal weaknesses that require attention include:

• Unclear economic regulatory mandate — a statutory framework that clearly defines economic regulation for shipping and port services, across terminals, pilotage, towage and stevedoring. Example: In Nigeria, multiple agencies overlap in regulating port tariffs and services. This often leads to conflicting directives. For instance, in 2019, freight forwarders protested contradictory tariff notices issued by NPA and terminal operators, causing confusion and delays in cargo clearance.

• Inadequate competition safeguards — rules to prevent anti-competitive coordination among dominant port service providers and to control discriminatory pricing or rebates. Example: Nigeria’s port system is dominated by a few terminal operators, and complaints of price-fixing and discriminatory rebates are frequent. In 2021, clearing agents accused some terminal operators of colluding to increase handling charges at Tin Can and Apapa ports, leaving shippers with little choice due to lack of competition.

• Opaque state support and concessions — legal rules for notification, transparency and competitive tendering for port infrastructure and concession contracts. Example: Since port concessioning in 2006, stakeholders have repeatedly raised concerns about the lack of transparency in concession renewals and state support. For example, concession agreements worth billions were renewed in 2021 without competitive bidding, prompting industry groups to call for more open tender processes.

• Weak dispute resolution mechanisms — specialised, speedy forums to resolve port commercial disputes and tariff complaints. Example: Disputes over port charges often clog Nigeria’s courts for years. In 2020, freight forwarders complained that unresolved tariff disputes were costing shippers millions in demurrage and storage fees as cases dragged on without timely resolution. This discourages smaller players who cannot afford prolonged litigation

Addressing these gaps will foster private investment, reduce trade costs, and increase government revenue through more transparent concessioning and predictable tariffs.

4. What strong laws should look like in practice

I propose a number of legal instruments and principles that should be considered:

• A Port Economic Regulation Act — a single statute that (a) defines the regulator’s objectives (promote efficiency, fair access and competition), (b) grants licensing and investigative powers, (c) empowers price monitoring and interim remedies where operators hold market power, and (d) provides for transparent rule-making and appeal.

The drive for this is already under way with the proposed Nigerian Port Economic Regulator Bill (NPERA Bill [currently awaiting Presidential assent]) where the Federal government seeks to properly equip the Nigerian Shippers Council, being the parastatal that is saddled with the responsibility of Port Economic Regulatory functions through A Presidential Order granted in 2015; to monitor pricing and provide for transparent rulemaking in the maritime industry. Singapore’s statutory model offers a helpful precedent .

• Competition law integration and sector guidelines — the existing competition law, namely the Federal Competition and Consumer Protection Act (FCCPA) 2018, must be applied to port markets. Where necessary, sector-specific guidelines (e.g., on rebates, bundling, exclusive deals) are produced jointly by the regulator (Nigeria Shippers Council) and the competition authority (FCCPC). The EU and UK frameworks show the importance of competition scrutiny in public support and port operations .

• State support transparency rules — We must require public notification of investment or support for port infrastructure, with objective criteria to assess compatibility with national economic goals and competition. The EU’s state-aid practice shows how transparency disciplines market distortions .

• Data, benchmarking and independent monitoring — The law must also require publication of performance metrics (dwell time, crane rates, berth productivity). Regular public benchmarking creates political incentives for reform and arms shippers with information. Australia’s port monitoring reports are a good example of how data drives policy .

• Specialised dispute resolution — We must also provide for expedited arbitration centre for port disputes, reducing transaction costs and providing predictable outcomes, encourages investment.

• Institutional Independence – Regulators must be financially autonomous, with leadership shielded from political pressure.

• Customs Facilitation Alignment – Implement the World Trade Organizations (WTO’s) Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) fully, leveraging digital clearance to reduce bottlenecks.

5. Linking domestic reform to our WCO Chairmanship

Nigeria’s chairing of the WCO Council places our customs leadership at the centre of global best practice on trade facilitation and customs governance. This international leadership must be mirrored at home: robust customs operations deliver little if the port economic framework remains permissive of rent-seeking and monopoly pricing.

By pairing WCO leadership with domestic legal reform we will:

• Demonstrate to multilateral partners and investors that Nigeria is committed to transparent, rule-based port governance;

• Improve trade facilitation outcomes — fewer delays, lower costs, better compliance — which benefits customs revenue collection and national competitiveness; and

• Leverage international best practice, technical assistance and harmonised standards through the WCO platform for domestic reform.

The world is watching Nigeria, and credibility abroad will only be matched by credibility at home.

6. Immediate recommendations

To convert law into outcomes I recommend these immediate steps:

1. Passing into law of the Nigerian Port Economic Regulatory Agency Bill — full stakeholder support.

2. Establish a data-driven monitoring programme — with quarterly KPI’s.

3. Adopt state-support notification rules — for infrastructure projects.

4. Strengthen enforcement capacity — through investigators and a specialist dispute resolution stream.

5. Enhance labour stability by fully implementing the MLC.

Conclusion

Strong law is not an end in itself. It is an instrument for creating predictable markets, for not only protecting shippers and consumers but also regulating providers and users of shipping and port services, for attracting productive investment, and for ensuring that public resources allocated to ports are used in ways that generate national income.

Nigeria’s elevation to the WCO Council Chairmanship is a moment of moral and political authority. Let us use that authority to cement our domestic institutions with laws that are clear, enforceable, and oriented towards competition, transparency, customs trade facilitation, safety, labour stability, and long-term national prosperity. Yet, it is pertinent to state that no matter how strong and beautiful our laws are, they cannot serve the purpose for which they were created without effective implementation measures. And implementation does not take place in a vacuum. The critical stakeholders in the industry must first acknowledge the binding force of these laws and accept that effective port economic regulation requires their full buy-in. Only when stakeholders own the process and elevate economic regulation as a collective priority can we truly facilitate trade and drive economic growth.

The regulator must also be perceived and respected as an impartial arbiter—ensuring equity and fair play among all industry players. With collective commitment and trust, we can restore confidence in Nigeria’s shipping and ports sector, unlocking the vast potential of our marine and blue economy for national prosperity.

If we do so, our ports will not only move more cargo; they will move our economy forward—our marine and blue economy sector will flourish and impact positively on the nation’s economy.

*Being a paper delivered by the Executive Secretary/CEO, Nigerian Shippers’ Council, Dr. Akutah Pius Ukeyima Esq. (MON, FCILT, FlnsTA, Ph. D) on the occasion of the 2025 one day seminar organised by the League of Maritime Editors on the 30th of September, 2025, at Rockview Hotel, Apapa, Lagos.